SPOILERS

AHEAD

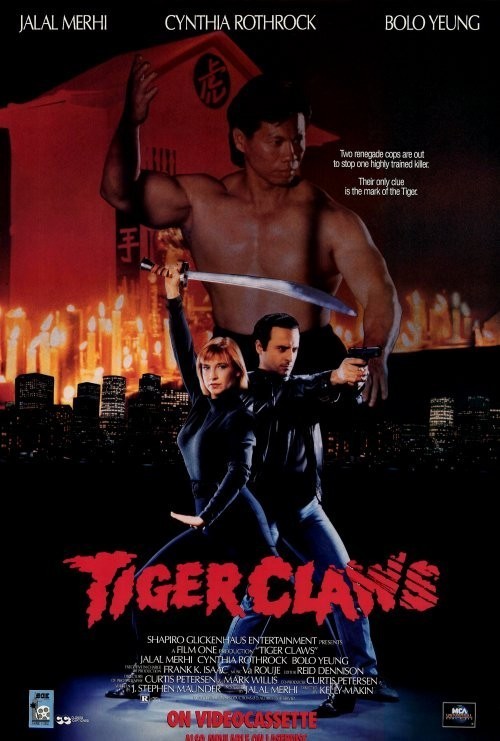

At

the end of the 80s, a Lebanese-Canadian martial arts competitor sold

his jewelry business and entered the world of karate flicks. His name

is Jalal Merhi, and through money and persistence, he became a staple

name of the U.S. video scene. Nicknamed “Beirut’s Steven Seagal”

(despite his accent making him comparable to Jean-Claude Van Damme),

what set him apart from virtually everyone else on the U.S. martial

arts scene was his desire to showcase Chinese martial arts over their

more common Japanese and Korean counterparts. He tried this first

with Fearless Tiger (1991), a

tournament flick that didn’t see an

American release until three

years after completion, but had greater luck with the more unique

Tiger Claws. Merhi’s

recipe for this endeavor?

– lots of kung

fu, established stars, and a capable

director. The result is a

thoroughly watchable adventure that grew on me over time. It’s an

examination of fanaticism in martial arts, and arguably the best film

Merhi would ever star in.

The

movie opens in New York City with a woman (Cynthia Rothrock) hounded

on the street by a suspicious man (Nick Dibley). He corners her with

evil intent, but she fights back and utterly decimates him in a

brawl, knocking him out before he’s arrested. It turns out she’s

Detective Linda Masterson, supercop, and the guy who attacked her was

a suspect in a crime spree. She’s disgusted that her wolf-whistling

partner (Fern Figueiredo) wasn’t anywhere to be found when the

fight happened, but more so that she’s wasting her time “dressing

up like a whore and working on these two-bit cases.” Shortly

thereafter, we meet our other hero: Det. Tarek Richard (Jalal Merhi),

who’s carrying out an undercover drug deal that, somehow, is also

the purview of rival detectives Roberts (Robert Nolan) and Vince

(Kedar Brown). It’s unclear who’s actually out of line, but

Tarek’s suspended when his counterparts initiate a fight/shootout

and the dealer is blown up in his car.

The

case they’re both headed for – Linda by intent and Tarek by

accident – is that of the Death Dealer, a serial killer targeting

martial artists. The victims’ claw-like head wounds lead Linda to

believe that the killer’s also a martial artist and that he can be

unconvered by identifying his fighting style. This impresses her

superior, Sergeant Reeves (John Webster), who assigns her to the case

over a sexist cohort but also demands she work with the

still-suspended Tarek. Linda’s not pleased but has no choice,

especially when Tarek promptly identifies the style as “fu jow . .

. some people call it tiger claw.”

Let’s

pause to examine the story’s unusual take on martial arts

awareness. Usually in these features, a martial artist is teamed up

with someone who has no such experience and thinks “chop socky”

is nonsense. That approach is subverted, here: Linda’s already a

master martial artist but still needs the insight of a “specialist”

like Tarek when it comes to exotic styles. Again, this is part of

Jalal Merhi’s unique formula: not only was he featuring kung fu in

his movies when few others were, but doing so at a time when these

styles weren’t even widely practiced outside of films. It’s less

of a deal now that Hong Kong flicks are widely distributed and it’s

easy to find modern kung fu fight scenes, but at the time, Merhi

capitalized on a market opening and used the opportunity to build up

the Chinese arts grandly. The movie’s stance is that, while you can

be a well-studied martial artist, there’s always more to learn by

looking to the past. If you don’t, you’ll be at a disadvantage.

This sentiment isn’t explored and thus feels a little like martial

arts propaganda (“Your kung fu is strong, but mine is better!”),

but I think Merhi was merely trying to set a precedent at this point.

Photo source | Jalal Merhi, Kedar Brown, Robert Nolan

Tarek

and Linda search Chinatown for the school where the killer trains.

Specifically, they’re searching for a secret studio that only

trains serious fighters – like Tarek says, “This is not a sport

for any bozo with 50 bucks.” They eventually receive a tip from a

drunken boxing student (Rick Sue) who they rescue from a gang

beating. It’s a cool fight, but doesn’t go very far in

distinguishing our heroes’ differing approaches to martial arts:

Tarek has some flowing movements, but he’s still as hard-edged as

his partner. Ironically, it’s Linda who wields a Chinese rope dart.

Anyway, they’re directed to a local tournament to find Sifu Chow

(Mo Chow) – the only fu jow teacher in the area. Tarek not only

finds him, but also an old friend and tournament competitor, John

Atkinson (playing himself). A huge and mysterious man in the crowd

(Bolo Yeung) looks on ominously as John wins the championship.

Shortly thereafter, he shows up in John’s home and attacks him –

killing him with a tiger strike to the face. Afterwards, we see the

guy before a tiger-themed altar decorated with trophies from the

other beaten martial artists. This is our killer.

Tarek

and Linda follow Chow to an abandoned movie theater which Tarek

immediately identifies as his school. He wants to go in right away,

but Linda demands he stay. When a night of waiting results in nothing

but the aforementioned death of his friend, Tarek impatiently sneaks

into the studio on his own. He’s promptly discovered, but –

immediately crafting his cover – earns a chance at tutelage by

revealing that Chow and he studied under the same master. (Stroke of

luck, huh?) Before leaving, Tarek notices his friend’s killer

painting a mural on the wall, but of course doesn’t know who Chong

is.

Photo source | Cynthia Rothrock, John Webster

TRIVIA:

A subsequent scene features Tarek and Linda arguing whether to go to

an Italian or Chinese restaurant to eat. This mirrors a real-life

event wherein Merhi, Rothrock, Yeung, and some production members

were deciding where to eat after a day of filming. Everyone voted for

Italian, with the exception of Yeung. Merhi, who idolized Yeung,

immediately changed his vote and attempted to sway the group in favor

of Bolo’s choice. He was overruled and the group went to the

Italian locale, where Yeung refused to order anything.

Tarek

returns to the secret studio and earns his spot

by holding his own in against the other students. This is the first

fully-fledged kung fu fight scene, and the difference to previous

brawls is noticeable. The pacing is more restrained and the tiger

claw choreography reminds me of classic Hong Kong fights. You

get the impression that the filmmakers are genuinely trying to make

the fu jow

aspects

stand out, and this continues as Tarek engages

in a necessity for

any

good kung fu

flick – a training scene. He twirls weapons, strikes form, and

toughens his hands by submerging them in a wok of boiling water

filled with chains. Sifu Chow doesn’t do much on-the-ground

teaching, preferring

to beat a drum while his students go

at it, but he does step in

as a rivalry between Tarek and fellow

student James (Ho

Chow) threatens to get out of hand.

In

an unexpected turn, another student (Gary Wong) invites Tarek to a

go-go club, and they take Chong with them. The movie twists

expectations by showing Chong as a normal guy who drinks and laughs

with his comrades, but eventually, the scene’s mainly there so

Tarek can find out how good of a fighter the muralist is when they

have to thwart a mafia attack on the joint. Additionally, Chong keeps

Tarek from killing one of the guys – highlighting the theme of

martial excess that I’ll get into later. In the aftermath, Tarek

still isn’t certain which of the practitioners is the killer, but

Linda thinks it’s the hotheaded James. She confronts him at a

billiard bar, and despite beating up him and half the establishment

in the process, it turns out that he has an alibi. This faux pas

results in Linda and Tarek being removed from the case and being

replaced by the insufferable Roberts and Vince. In the meantime,

Chong kills Sifu Chow and some of the students.

Photo source | Bolo Yeung

This

scene is an enigmatic as it is essential. The final exchange between

Chong and Chow features Chinese dialogue with no subtitles, so while

their exchange may offers clues to Chong’s motives, I can’t be

certain. We

don’t find out otherwise

why Chong is a serial killer. The head-spinning

sequel throws a ton of new, outrageous information into the

continuity, but where only

this movie is concerned, it’s

ambiguous. The only theory

that’d

tie into

an existing theme is that Chong, having taken his training to the

extreme, has literally been driven crazy

by kung fu. Tarek’s spent the picture making sure we know how

demanding and encompassing fu jow is, having mentioned that his wife

left him when last

he trained – implying that

he, like Chong, has the potential to become a menace if

not kept in check. Tarek’s

also the only character to voice a

theory on Chong’s motives, saying that perhaps he’s

trying to “drum up lost respect for his style.” This may in fact

be a part of the reason,

given how the movie venerates

kung fu. Chong may see his

victims and

their martial arts as temporary and weak and is thus trying to

exemplify

the “true” martial art. This isn’t entirely without real-world

parallel: fierce inter-style

competition goes back centuries, and Chinese styles have often been

ridiculed in modern times

by “hard style” practitioners for being impractical and fancy.

Altogether, this information

comprises pieces to Chong’s puzzle, but the picture still isn’t

clear. Perhaps that’s why the movie reveals the killer relatively

early: it’s not bad writing, but an intended opportunity for

viewers to ponder Chong’s motives.

Tarek

and Linda refuse to drop the case, and they somehow

determine that Chong is their

prime suspect. Their suspicions are confirmed when they enter the

studio, finding the others

dead and Chong in attack

mode. He flees after a quick

duel with Linda, who spends the rest of the night searching for him

with Tarek. They find him at the pier, but not before the bumbling

Roberts and Vince arrive and handcuff

Tarek, suspecting him of the murders. Linda and Chong fight again –

possibly the best one-on-one match of the film – but the finale

pits the still-handcuffed Tarek against Chong in a warehouse. In a

bit of egoism, Jalal Merhi’s character is able to best Chong while

spending the majority of the fight with his hands bound. The

film ends with with Chong apprehended, Tarek and Linda commended, and

the former reinstated while the two share an awkwardly-earned

kiss on Tarek’s boat.

Photo source | David Stevenson

TRIVIA:

The movie draws on real-life characteristics for many of its

characters. For example… Linda is from Scranton, PA and

Chong is from Canton, China – just like their actors. Jalal Merhi

wasn’t divorced, but like Tarek, he was single at the time of

production. John Atkinson was indeed a successful karate fighter and

multi-time grand champion. Mo Chow is a martial arts

instructor who operates his own studio.

Bill Pickels – Chong’s first victim – is a former cable TV

personality in Canada. Three actors share similar or identical names

with their characters: Mo Chow, John Atkinson, and Bill Pickels.

I

wasn’t a Jalal Merhi fan when I first saw this, and only held onto

the tape for Cynthia Rothrock. I can still see why the guy didn’t

click with me right away. Merhi lacks the charisma that makes even a

questionable actor like Rothrock fun to watch, and despite his

emphasis on kung fu being genuinely unique at the time, it doesn’t

make him stand out to the average viewer. Despite his efforts, Merhi

isn’t comparable to Steven Seagal introducing aikido in the late

80s or Tony Jaa rewriting action choreography with muay thai in the

2000s. Nevertheless, the more of this subgenre you consume, the more

Jalal’s effort does in fact stand out. The Chinese martial arts

help give this movie a unique flavor that you won’t find in other

kick flicks of the same budget. The crisp forms, traditional uniforms

and decent training montages eventually give the movie an air of

importance that I kind of miss in other features. This approach won’t

click with viewers who’d rather limit martial arts exclusively to

fight scenes, but it might be unique enough for those who’ve grown

tired of repetitious kickboxing.

Merhi’s

use of eye-catching names to star alongside him is a sound decision,

but again, you can’t help but chuckle at the scene that features

him defeating Bolo Yeung as Cynthia

Rothrock fishes a buffoonish

detective out of the bay.

Nevertheless, treating his own

character as exemplary

doesn’t mean the others are treated as jokes. This is one of

Yeung’s most interesting non-Hong

Kong roles, and even though

Rothrock hangs back many

times, both she

and Bolo are given ample

opportunity to steal the show in

fight scenes. To tell the

truth, Merhi is

elevated by their presence because

they bring out a lot in him. I’ve seen the guy do flashier moves,

but he’s never looked as tight and collected as he does here. To

date, Merhi is the only Arab martial arts star who’s had a solo

career in North America, and he really puts his best foot forward in

making a first impression here.

Exploring

the martial arts theme yields contradictory results. We’re to

presume that fu jow – and “old” martial arts in general – are

superior to modern forms, because when they come into contact, the

former tends to triumph. Nevertheless, Linda seems to be the

exception: she isn’t versed in fu jow but still defeats a hardcore

practitioner in direct combat. We’re also led to believe that

respect and mastery of the martial arts is limited to the experience

of immigrants and minority characters, but the majority of Chong’s

victims fall under the same labels. There’s also a theme of martial

arts bringing people together – i.e. Linda and Tarek bonding over

their practice of the fighting arts – but this ignores that Tarek’s

wife left him because of his training and that Chong’s obsession

with the martial arts may be the cause of his murderous behavior. I

wish the film were more consistent in what it’s saying.

Nevertheless,

it’s still enjoyable and that’s got much to do with director

Kelly Makin. Merhi had a knack for selecting inexperienced directors

who’d later go on to critical acclaim, and Makin displays his

talent via style in what would otherwise have been a humdrum-looking

picture. Though I’m not sure whether anyone would think this is an

A-grade production, Makin delivers a consistently clean look and

takes time to highlight the soundtrack, indulge in interesting camera

angles, and even film an occasional arty establishing shot. Though

not the best in this regard, he can shoot a fight scene surprisingly

well.

Tiger

Claws is a

fun watch for genre fans and definitely worth

hooking up the old VCR for. The

cast is a supergroup of genuine martial talent and

the filmmakers

know how

to make them shine. There are plenty of things I’d change, but

overall, this is one experiment that pays off. People interested in

coming into these types of movies should definitely consider it, and

established viewers

who’ve yet to see this particular one shouldn’t hesitate much

longer. Check it out!

Tiger

Claws

(1991)

Directed

by

Kelly Makin (Mickey

Blue Eyes)

Written

by J.

Stephen Maunder (writer for almost all of Jalal Merhi’s movies)

Starring

Jalal Merhi, Cynthia Rothrock (China

O’Brien),

Bolo Yeung (Bloodsport),

John Webster

Cool

costars:

Gary Wong, Michael Bernardo (WMAC

Masters),

Rick

Sue (Expect

No Mercy),

David Stevenson (Death

House),

Bill Pickels (Sworn

to Justice),

Mo

Chow (Talons

of the Eagle)

and Ho Chow

(Kung

Fu: The Legend Continues)

are

all legitimate martial artists playing the part. Wing chun legend

Dunn Wah (AKA Sunny Tang) plays a master

but doesn’t have

any fight scenes. IMDb credits gang member William Cheung as the

William

Cheung – kung

fu

master and contemporary

of Bruce Lee

– but I don’t think they’re the same person. Similarly,

John

Atkinson is identified as an English TV actor who died in ‘07,

whereas the real performer currently operates a martial arts studio

in Arizona. Robert

Nolan

(Sixty

Minutes to Midnight)

is

a fairly

acclaimed dramatic

actor

while his onscreen partner

Kedar Brown has

been building a career in

voice acting.

Content

warning: Sexist

dialogue, attempted

sexual assault, group

violence, WTC imagery

Copyright

Tiger Claws Productions, Ltd. / MCA Universal Home Video (now

Universal Pictures Home Entertainment)